What the FFIS Results Might Tell Us About Regional Balance

From an advisory point of view, much of today’s discussion across the rural sector has centred on the Future Farming Investment Scheme (FFIS) results. No one was surprised that it was heavily oversubscribed — that was expected from the outset. What has caught people’s attention, though, is how the approvals have been distributed and whether the weighting and scoring metrics were applied in the way many assumed they would be. Those questions are fair ones, and worth exploring.

The Future Farming Investment Scheme (FFIS) has been one of the most talked-about support measures this year. Open for just over a month during the summer, it offered capital grants to help farmers and crofters invest in their businesses — anything from improving efficiency and sustainability to supporting environmental goals and cutting emissions.

In theory, it was a broad and inclusive scheme. Smaller holdings could apply for up to £5,000, medium-sized units up to £10,000, and larger holdings up to £20,000. Funding could cover 100% of eligible costs, but everyone knew from the start that demand would be intense. With an indicative budget of £14 million and thousands of applications expected, many good projects were always going to miss out.

What made this scheme stand out was the promise of weighting — giving a helping hand to applicants who might otherwise find it harder to compete. The guidance said additional consideration would be given to new entrants, young farmers, tenants, small businesses, organic producers, and island-based agricultural businesses. That last point — the islands — is an important one, because those areas face higher costs and fewer options when it comes to investment.

Early figures doing the rounds

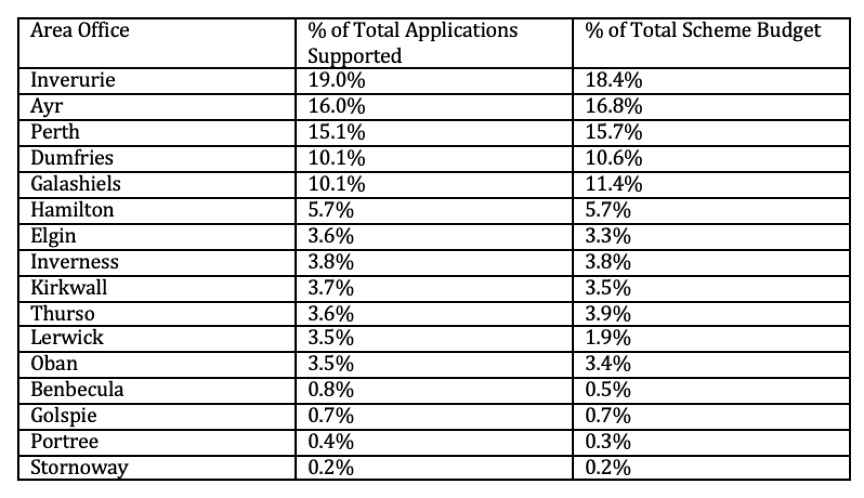

Now that decisions have been issued, there’s a lot of chat about how the approvals were distributed. A table has been circulating that appears to show how successful applications and total funding were split between area offices. These figures haven’t been officially published, so they should be treated with caution — but they give an early sense of how things might look.

From this early picture, it looks like a small number of area offices — mainly Inverurie, Ayr and Perth — account for well over half of all the approved applications and total budget. In contrast, island and remote offices such as Benbecula, Portree and Stornoway make up only a fraction of the total. Even within the islands, there are some interesting differences: Lerwick has a decent share of approvals but a smaller share of total funding, suggesting smaller average grants.

The reality of a competitive pot

Before jumping to conclusions, it’s worth remembering that this was a competitive pot. The number of applications was always going to far exceed the money available, and that means a lot of good projects were inevitably turned down. The regions with more applications were always going to see more approvals in simple numerical terms.

But the weighting system was meant to help balance that — to make sure that small businesses and island communities weren’t squeezed out by sheer volume from bigger, better-resourced farms elsewhere. If the data above turns out to be accurate, it’s fair to ask whether those weightings made much practical difference.

What this really shows

Rather than speculating about why the results look this way, what’s really needed now is clarity. The key question isn’t just which regions received more or less — it’s how the scoring and weighting were actually applied. Without that transparency, no one can know whether the outcomes reflect regional demand or whether the system simply didn’t deliver balance as intended.

We also need to see the application-to-approval ratio for each region. That one figure alone would tell us a lot about whether certain areas had disproportionately low success rates. The early data suggests that the weighting for island and smaller businesses has not have fully translated into results on the ground — which is precisely why clear reporting is essential. It’s not about criticism, at least not yet, but about learning whether the system worked as designed.

Why it matters

Schemes like FFIS are about more than funding equipment. They’re about confidence — the sense that the process is fair and that rural communities are genuinely being supported. If certain regions, particularly the islands, consistently come out with a smaller share, confidence is undermined. And once confidence is lost, it takes a long time to rebuild.

That’s why transparency matters. Publishing the regional breakdowns, alongside the scoring criteria and how weighting was applied, would help everyone understand what actually happened. If the system worked fairly, the numbers will speak for themselves. If it didn’t, that’s important feedback for improving future delivery.

Looking ahead

For those who applied but were unsuccessful, there are still a few steps that can be taken. Applicants are entitled to request feedback on how their application was scored — and it’s worth doing so. Understanding where points were gained or lost can help strengthen future bids. For crofters, there remains support available under the Crofting Agricultural Grant Scheme (CAGS), which continues to fund practical improvements and infrastructure investments.

More broadly, this round of FFIS highlights a wider issue the rural sector can no longer ignore: the need for a clearer, more transparent approach to how support schemes are designed, scored, and delivered. It might now be time for the sector — crofting, farming, and advisory bodies alike — to speak with a more united voice in calling for better systems, or to present alternative ideas to government, and making them listen, about how grant funding can be delivered more appropriately to serve the diversity of rural Scotland.

Update: New data highlights possible inconsistencies in weighting outcomes

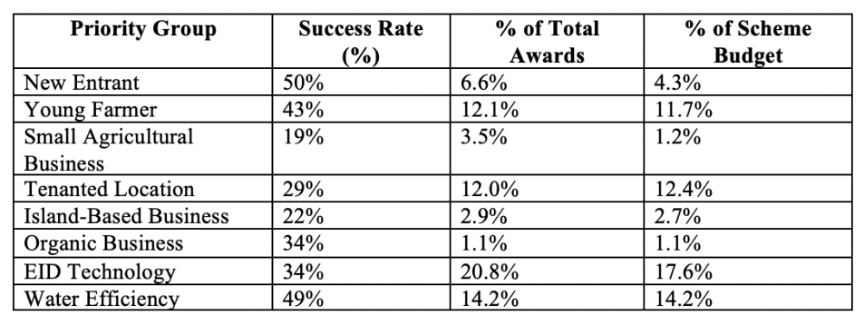

Since this article was first published, further figures have begun circulating within the sector that offer more insight into how the FFIS awards were distributed across ministerial priority groups.

At face value, the data suggests some clear patterns — and some worrying inconsistencies — in how the weighting criteria appear to have been applied.

These figures tell their own story. While new entrants and young farmers performed relatively well, other key priority groups — particularly small agricultural businesses and island-based enterprises — achieved far lower success rates and received a fraction of the overall budget share.

Even tenanted holdings, long recognised as needing fairer access to capital support, received less than a third of their applications approved.

By contrast, the bulk of funding went toward EID technology and water-efficiency investments — project categories tied to specific equipment types rather than business structure or geography.

This pattern suggests that, in practice, investment type outweighed applicant type, and that the intended ministerial weightings for smaller, island, and tenant businesses may not have had the expected impact.

Without full publication of the scoring matrix and regional application data, it remains impossible to confirm whether the weighting criteria were consistently applied. But based on the available information, the results do appear at odds with the stated aims of balancing opportunity across farm size and location.

For a scheme that promised inclusivity, that gap between policy and outcome deserves open discussion — not to assign blame, but to ensure future programmes deliver on their intent and rebuild confidence across the sector.